While largely hidden from view, the modern braking system is absolute high-tech. That hasn’t always been the case. In the early days of the car, the brakes were even simpler than those of a bicycle; a block against the tire had to provide deceleration.

The first cars at the end of the nineteenth century shared much of their technology with the carriages and coaches of those days. It’s all simple and straightforward, including the braking system. Where the term ‘system’ suggests more than it actually is; the braking system of a modern bicycle is already a lot more advanced than that of those first cars. With the Benz Patent-Motorwagen Number 1, deceleration is achieved by manually operating a lever that tightens a brake band around a disc in the driveline. In essence, this is an inside-out drum brake. With the modest speed of that car, this provides acceptable deceleration. Unfortunately, the belt is subject to heavy wear and tear and is not destined for a long life.

In later models, Carl Benz comes up with another solution: blocks that can be pressed against the tread of the wheels. The principle dates back to antiquity and is not very refined, but it provides enough friction to bring the vehicle to a standstill. Well-known is the story of Bertha Benz who, on a summer Sunday morning in 1888, left early with her husband Carl’s Patent-Motorwagen 3 from Mannheim for a family visit in Pforzheim. Along the way, she knocked on the door of a pharmacy in Wiesloch for gasoline. The latter has gone down in the history books as the first gas station. Less well known is that she then stops a little further on in Wiesloch again, now at a shoemaker. The brake pads of the Patentwagen are already so worn out during the first leg of the trip that Bertha asks the shoemaker to nail leather onto the blocks. This unplanned action is the invention of the brake lining.

Drums prove to be a sustainable alternative

The road network is not as tight and well-maintained in the pioneering phase as it is today. It is mostly unpaved, often dirty and muddy. That has its effect on the brakes, especially when it is also wet. At ever-increasing speeds, an open construction, especially if the tread of the tire has to serve as friction material, is far from ideal to ensure reliable and uniform deceleration.

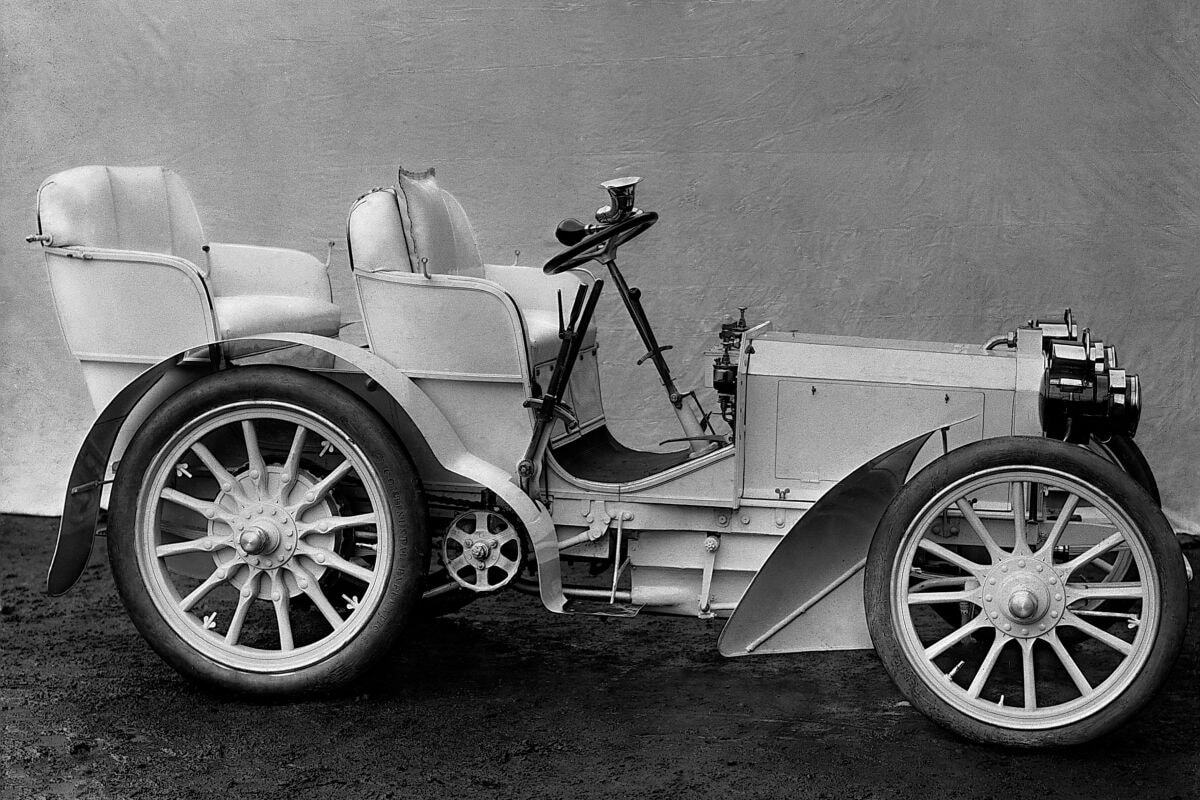

A sustainable alternative proves to be the drum brake. That closed drum was already patented in 1882 by Walter Russel Mortimer. Yet it takes until 1900 for the drum brake to find its way into the car. The first car with drum brakes is the Mercedes 35 PS. Those drums are only on the rear axle and the operation is still done manually, with a lever plus a system of rods. Incidentally, that 35 PS does have a foot brake, but it works on the drive shaft – and thus also on the rear wheels. To prevent overheating, those first drum brakes on the Mercedes have water-cooled brake shoes, a construction by Wilhelm Maybach, who, by the way, does not apply for a patent for it. Other car manufacturers are already picking up on the drum brake. So does Louis Renault, who does apply for a patent on a number of parts of the drum brake in 1902.

Ferodo: friction material

Meanwhile, Englishman Herbert Frood has been working on the development of friction material for various applications since 1897. In a watermill-powered test setup, he experiments with numerous materials. In 1908, he came up with asbestos fabrics reinforced with copper wire. This proves to be not only wear-resistant enough, but also resistant to high temperatures such as those that occur in drum brakes. The heat-resistant asbestos brake linings make the drum brakes a lot more reliable. For the name of his company, Frood shuffles the letters of his last name and adds the first letter of his wife Elisabeth’s name: Ferodo, still one of the leading companies in the world of brake pads.

Heat development during frequent or prolonged use has, among other things, the consequence that the drum expands slightly and thus gets a larger diameter, resulting in a longer pedal stroke. Self-adjusting brakes offer some relief, although that does not always work equally on all four wheels. The high temperature also influences the properties of the friction material, the friction decreases. Furthermore, excessively hot brakes can cause vapor lock in the brake fluid, so that when you press the brake pedal you do not put pressure on the brake shoes but only compress the air bubble. Very undesirable.

A solution to suppress the high temperatures is to increase the drum dimensions, but that entails more mass. In the case of the brakes, that is unsprung mass and that is unfavorable for road holding. But well, as a constructor you have to do something. Another solution to get rid of the heat is cooling fins on the drums, as Mercedes used on the 300 SL, for example.

Cables and pipes, first hydraulic braking system on Duesenberg

In those first decades, the drum brakes are operated entirely mechanically, with rods, cables and springs. In addition to the fact that these constructions deteriorate quickly due to rust and dirt, wear and tear and resulting play lead to less accurate operation. Accurate adjustment is vital because otherwise the car will pull to one side. An answer to this comes in 1921, the Duesenberg Straight Eight, with an eight-cylinder in line, is then the first production car with a hydraulic braking system, developed by aviation pioneer Lockheed.

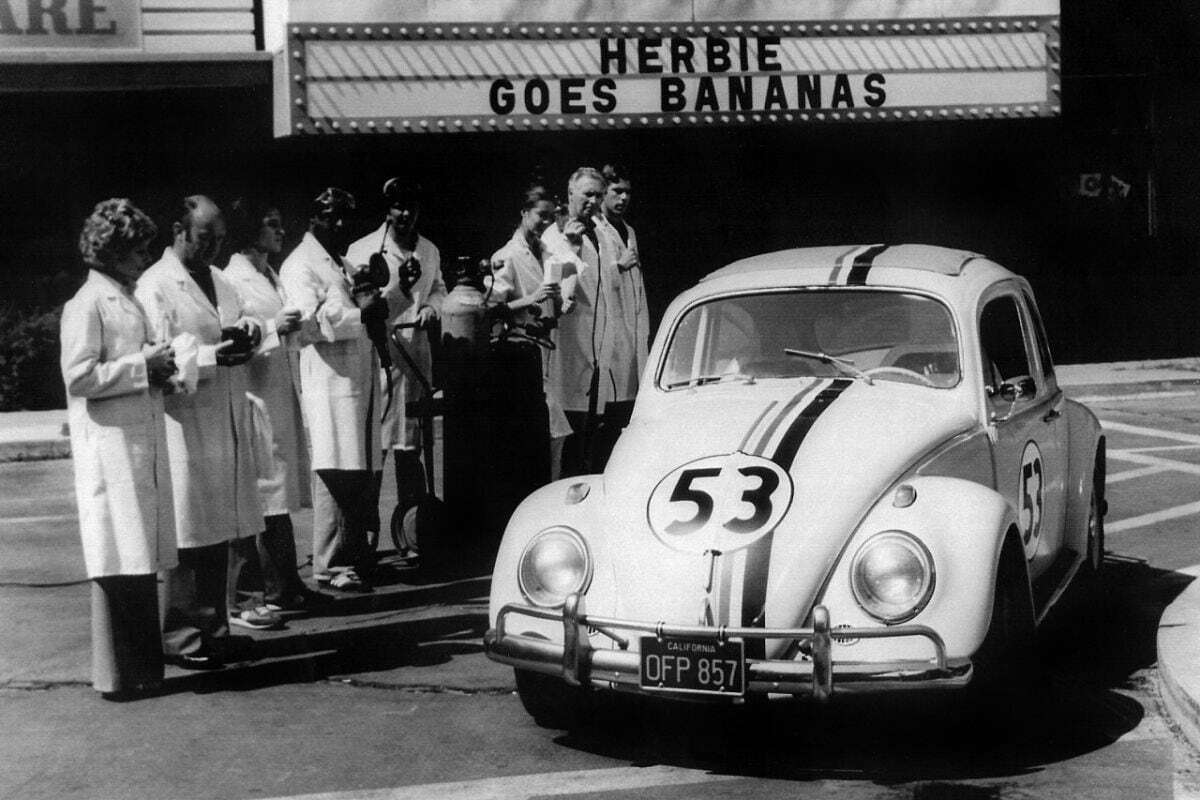

As quickly as the drum brake was embraced at the time, this is not the case now with the hydraulic braking system. It is not until the course of the 1930s that it finds wider application, and certainly not immediately in the cheaper cars. For example, the Volkswagen Beetle initially has cable-operated brakes, only from May 1950 do the export versions get a single-circuit hydraulic system, while the basic version simply has to do with cables until April 1962. For the handbrake, the cable remains the standard technique for most brands until the 21st century, even if it is electronically controlled.

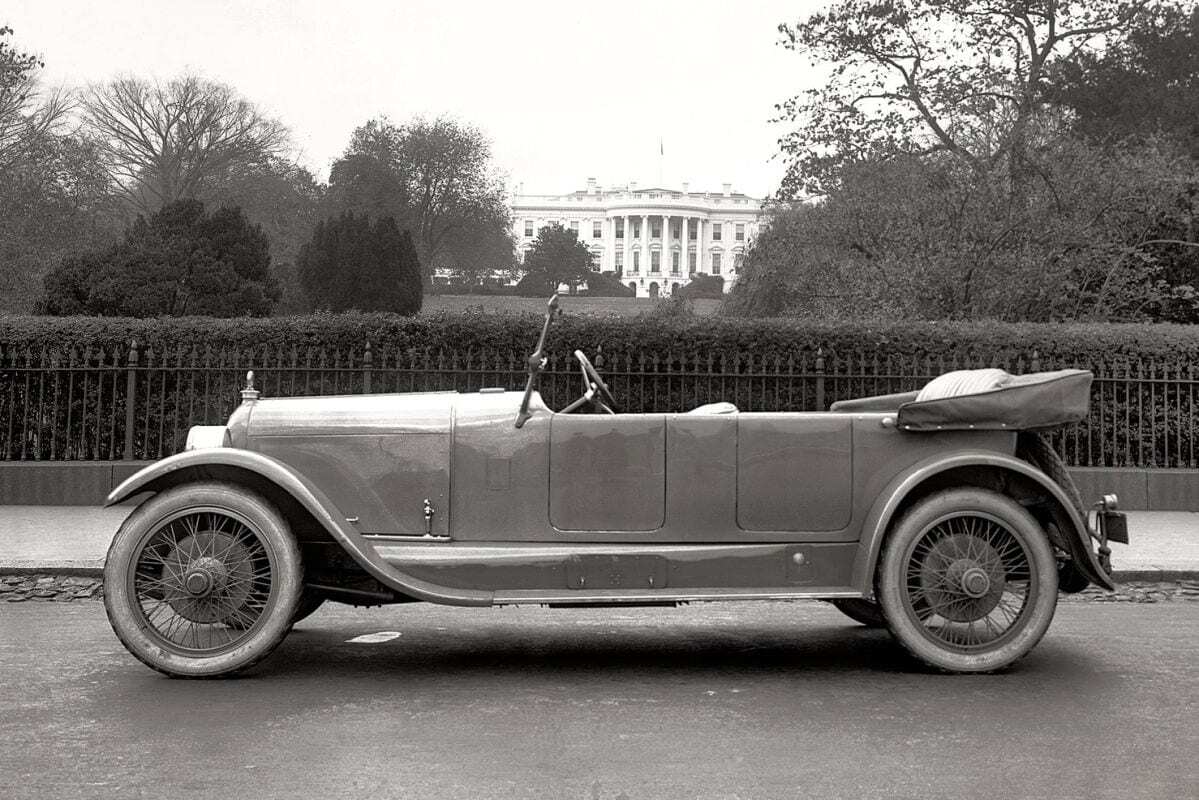

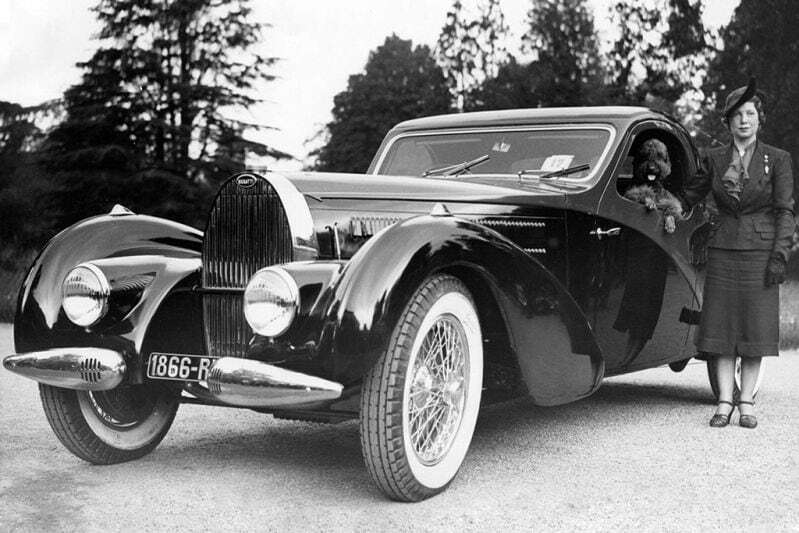

Alfred Teves applies for a patent in 1930 for a braking system separated into two parts. One hydraulic circuit operates the front wheels and one circuit operates the rear wheels. Should leakage occur in one circuit, it is always possible to fall back on the other (albeit less powerful). To give substance to this principle, Vincent Hugo Bendix develops a tandem master cylinder for it, for which he received a patent in 1934. The Bugatti Type 57 is the first car in 1938 with such a master cylinder. The Saab 96 gets a diagonally separated braking system in 1963: one circuit operates the front right and rear left, the other front left and rear right.

Subsequently, the Volvo 144 in 1966 is the first with a triangle-separated braking system, in which each of the hydraulic circuits operates both front brakes plus one rear wheel. When one circuit fails, 80 percent of the braking power is still available. The rest of the auto industry quickly follows and this solution remains the standard for more than half a century.

Shining discs

An alternative to the drum brake is the disc brake. Manufacturers and technicians are already researching it in the early days of the car, an important pioneer is Frederick William Lanchester. The stumbling block around the turn of the last century is suitable material. Ferodo doesn’t have anything yet and so it is metal on metal: copper blocks on iron discs, which, in addition to a lot of wear and tear and mediocre performance, also produces a lot of noise. In the interwar period, the disc brake does cautiously find its way to the railways and just before the Second World War, Daimler uses a system from Girling for an armored car. Here disc brakes are more or less necessary because the 4×4 drive of that military vehicle does not offer space for drums.

After the war, manufacturers experiment with disc brakes left and right. Between 1949 and 1953, the Chrysler Crown has a system with two discs per wheel, enclosed in a cast iron drum. When you brake, the discs slide outwards, against the sides of the drum. Just when Chrysler dismissed this heavy and complicated system in 1953, Austin-Healey in England came up with the 100S with disc brakes all around, a conventional system as we still know it with calipers and pads.

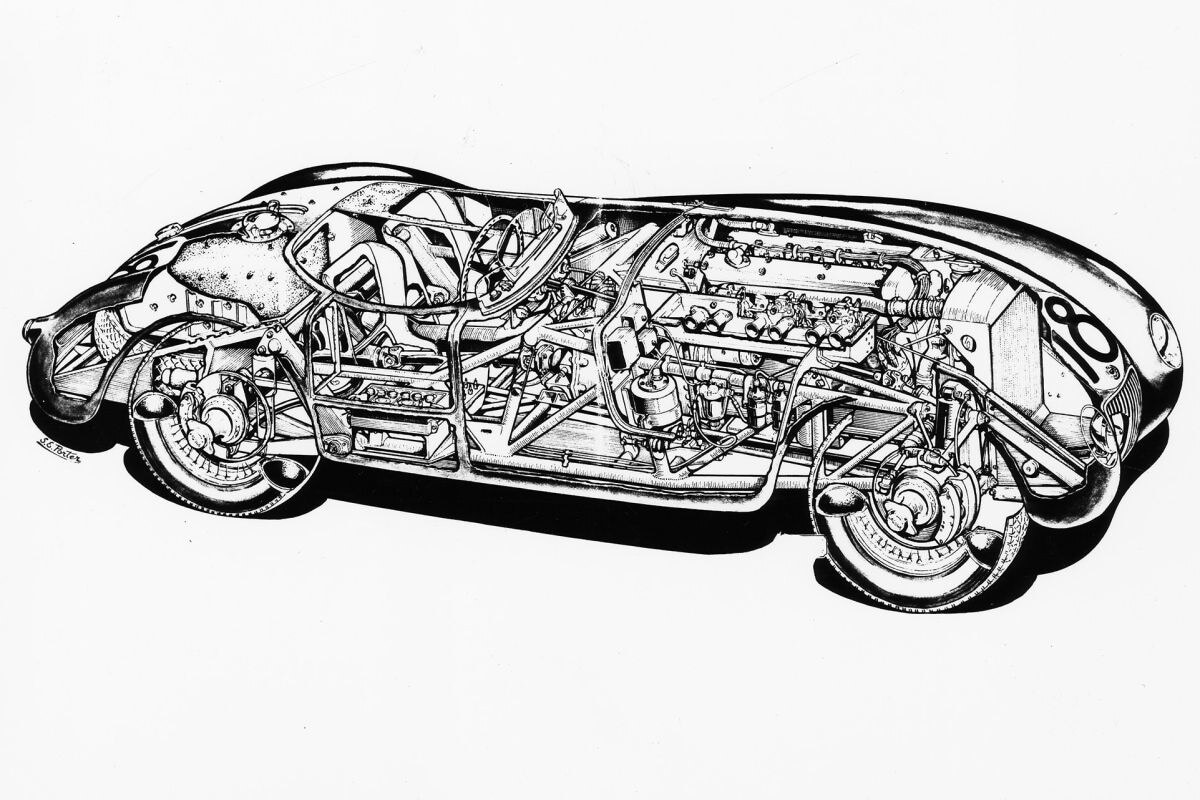

Interest in the disc brake receives a boost in 1953 mainly thanks to Jaguar, which that year wins the 24 Hours of Le Mans with the C-type, the only car in the field with disc brakes. Thanks to the reliability, their constant braking performance and the confidence that the disc brakes inspire in the drivers, that C-type is the first car to win ‘Le Mans’ with an average speed of more than 160 km/h (100 mph). Incidentally, it still takes until 1957 for the disc brakes to appear on street cars at Jaguar, namely on the XK150. In large volumes, the disc brake is already available for two years in the futuristic Citroën DS.

The disc brake has a number of advantages over the drum brake. Besides being more resistant to higher temperatures, it delivers more consistent performance and is more economical to maintain. Replacing brake pads is faster than changing the brake shoes of a drum. But with increasing load, both in motorsport and on the street, as a result of ever higher weights and greater performance, disc brakes are also becoming increasingly heavily loaded over the years. Coping with that extra load is accompanied by significant heat development and that is unfavorable for both the lifespan and the performance. With holes (straight through the disc), grooves (in the disc surface) and internal cooling channels (from the heart to the circumference of the disc), it is in any case possible to suppress high temperatures for everyday use. In addition to cast iron, we also see carbon and ceramics, materials that are much more resistant to heat.

Ready for the future with ABS

Now that the braking system is becoming more reliable and easier to control, new challenges follow. How to prevent those eager brakes from locking the wheels, making the car uncontrollable? The aircraft industry has been experimenting with mechanical anti-lock braking systems since the 1920s. At the end of the 1960s, the big three in Detroit, together with the brake parts supplier Bendix, also focused on a mechanical ABS.

However, ABS only became a success in 1978 when the Mercedes-Benz S-class gets an electronically controlled ABS from Bosch. It is the prelude to a braking system that can ultimately be fully electronically controlled. That is useful, because by controlling the brakes separately per wheel, the electronics are able to adjust the car or stabilize it in the event of impending slip danger. Furthermore, an electronically controlled braking system proves ideal when getting acquainted with cars with (plug-in) hybrid and fully electric powertrains. Those HEVs, PHEVs and BEVs are even more efficient when they can recover braking energy. When braking, the electric motor initially works as a dynamo that converts kinetic energy into electricity that is fed back to the battery. That usually works up to decelerations of about 0.3 g (approximately 3 m/s²). For reference: in an emergency stop, the average car has a deceleration of 1 g, almost equal to the gravitational acceleration on mother earth of 9.8 m/s².

Up to decelerations of 0.3 g, the mechanical brakes do not have to do anything. Those mechanical brakes are not always discs these days. For cost reasons, we still regularly see drum brakes behind the rear wheels, such as, for example, in the fully electric Volkswagen ID3. At decelerations greater than 0.3 g, the mechanical brakes assist or take over completely. The electronics regulate (or at least attempt) that the transition from regenerative to mechanical braking is seamless. If that is possible at all. When the battery is still too full to absorb regenerated energy, the mechanical brakes must already come into action immediately, even at decelerations of less than 0.3 g. The electronics regulate that without you noticing it much. Anyway, the electronics as part of the ADAS system is able to give a braking command outside of you, for example in case of emergency or as adaptive cruise control.

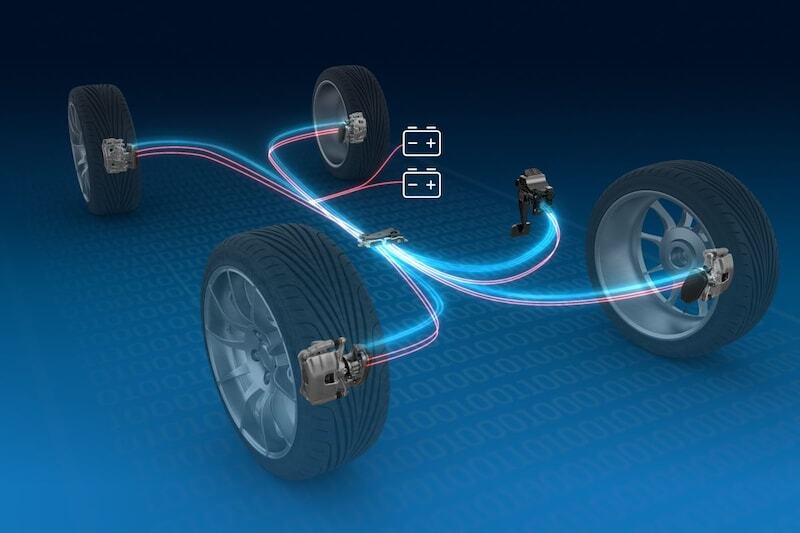

With the advent of electronics, the hydraulic braking system seems to have had its day. The future is brake-by-wire. With electronics that are able to operate the brakes themselves, the first steps have already been taken. The next step is the transition to a so-called ‘dry’ system. Here, no command is needed to build up hydraulic pressure, but electric motors regulate via a spindle that presses the brake pads against the brake disc. This is already being used as a parking brake and with the increasingly accurate electronics, it is also becoming easier to implement the service brake in this way. All in all, the dry system is less complex and therefore cheaper, but also requires less maintenance. Could Bertha Benz have imagined this when she knocked on the shoemaker’s door?