ADAS, or assistance systems, have undergone a long development process, but they have now become so refined that they are part of the standard equipment of the car, just like the rear fog light or the horn. Many of these aids have the braking system as their basis, whether or not activated by electronics.

New cars are now standardly equipped with assistance systems that make life easier and, above all, safer. These are not gifts from the car manufacturer: most of these systems have been legally required since last year. With camera, sensor, and radar technology, the car has been given eyes and ears that continuously, without getting tired, have to keep an eye on the surroundings. And also you as the driver. We are talking about Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS). If necessary, these ADAS adjust the direction and the tempo – they are essentially the first steps towards the autonomous driving car. In addition, they give you a warning that you need to stay focused, or they inform you that things are happening around the car that require more attention.

ADAS must help to halve the number of traffic deaths by 2030

The ADAS must make a significant contribution to the European goal of reducing the number of traffic deaths in the EU by half in 2030 compared to 2019. Whether this ambition is realistic? Independent organizations such as the European Transport Safety Council (ETSC) also see a downside to ADAS: with a digital safety net, drivers can also feel too safe, which can lead to complacency or even overconfidence. According to the ETSC, we are still far from on schedule for the 2030 goals. But well, for last year the ADAS were of course not yet mandatory. Because perhaps a step in the right direction is still being taken. The study ‘Safety effects of advanced driving assistance systems’ carried out last year on behalf of Rijkswaterstaat is in any case hopeful: the largest part of the systems has a positive effect. According to the report, the greatest impact on the number of accidents is due to Forward Collision Warning (FCW). With this warning for a collision at the front, a reduction in the number of accidents should be achievable that lies between 12.0 and 13.2 percent. The automatic emergency braking (Autonomous Emergency Braking, AEB) is a good second with an expected accident reduction that lies between 10.7 and 11.8 percent. An effect of 10 percent is expected from the Driver Monitoring System (DMS).

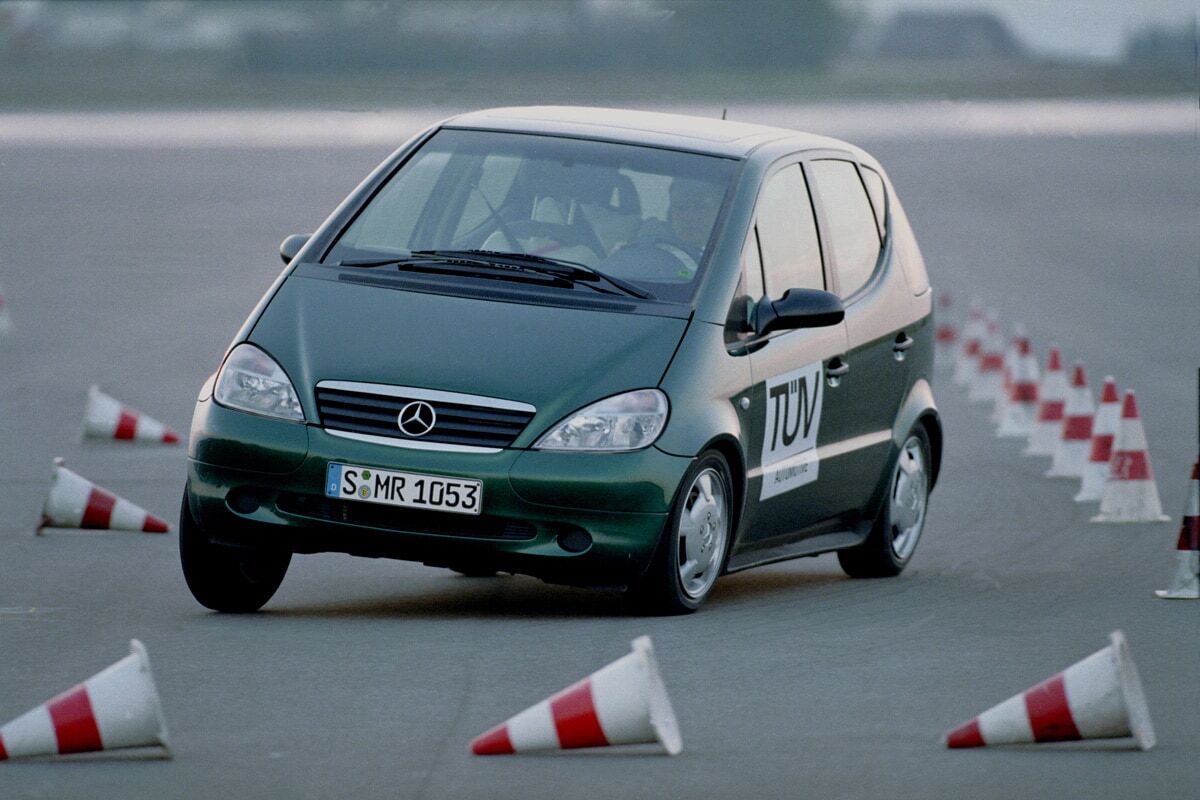

Mercedes-Benz S-class with and without ABS.

ADAS history begins with Mercedes-Benz

The history of ADAS begins in 1978 with Mercedes-Benz with ABS, later followed by the anti-slip control ASR (1985) and the electronic stability program ESP (1995). These are electronic systems that ensure that the car remains controllable and on course based on braking interventions. The basic information for ABS and ASR still comes very basic from the wheel sensors. They measure the speed per wheel: how often do the teeth of a toothed wheel pass a sensor.

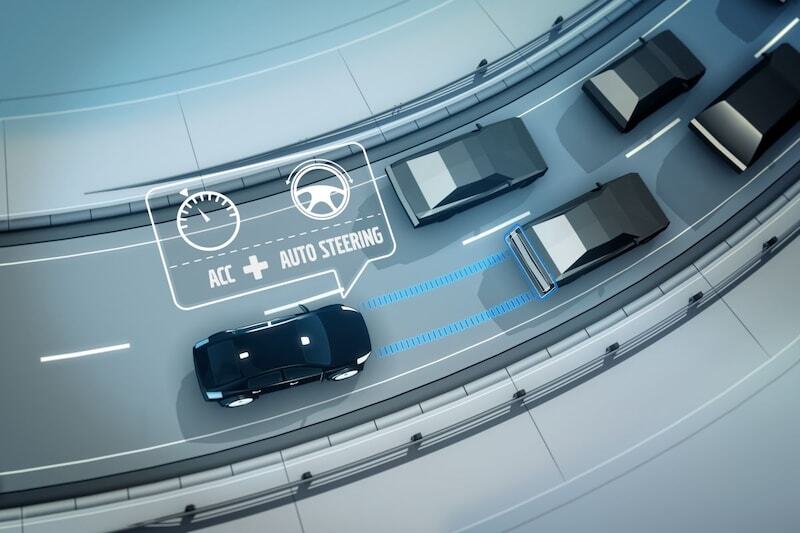

Meanwhile, Toyota comes in 1982 with ultrasonic parking sensors (based on sound waves) for the Corona. They do not intervene, but do warn. ESP builds on the ABS and ASR technology and adds a yaw angle sensor, which measures how much the car rotates around its vertical axis. Three years after ESP, the adaptive cruise control (ACC) finds its way to the showroom, initially the Mercedes showroom. With this, another sense makes its entry: the radar. It determines the distance to the vehicle in front based on radio waves (electromagnetic radiation). If that distance becomes too small, the gas is automatically reduced or the brakes come into action. These brakes are now also activated without ACC being switched on if the AEB detects an obstacle in front of or behind the car. The car is getting more and more eyes and ears; after the radar and ultrasonic parking sensors, cameras appear (now enough to look 360 degrees around the car) and extra information comes in via GPS.

In 2004, BLIS debuts on the Volvo XC90: the Blind Spot Information System, also known as the blind spot warning system. Cameras under the exterior mirrors on either side of the car monitor whether other road users are driving there. And if that is the case, a warning light lights up next to the relevant exterior mirror. And the end is not yet in sight. Take, for example, the Volvo EX90, which already has a lidar system on board. Lidar stands for Light Detecting and Ranging and, like a radar, measures the distance to an object. Only where radar works with radio waves, lidar does that with laser light. This has the advantage that measurements can be taken over a large distance (Volvo says up to 250 meters) and, above all, more accurately. This makes it possible to detect smaller objects.

First car with Lane Departure Warning System: Nissan Cima

All that information and signals lead to more and more functionality. In 2001, the Nissan Cima, the Japanese variant of the Infiniti Q45, is the first car with a Lane Departure Warning System (LDWS). In Europe, we have to wait until the Citroën C4 appears in 2004 before we are warned when we – without indicating – come close to the road markings. A next step follows with the arrival of electric power steering at the end of the zeros, then the electric motor makes its appearance in the steering system. With this, the car can now also independently perform steering corrections when you threaten to leave the lane. Although there is still a long way to go, this is a serious step towards autonomous driving. The sequel to this is the lane assistant who keeps the car neatly in the middle of the lane, or makes a brave attempt to do so. These systems are rapidly maturing and in the course of the second half of the previous decade it is already possible at Tesla and Mercedes to have the car independently change lanes by tapping the indicator lever, whereby the car not only keeps course neatly, but especially first looks carefully whether it is safe to do so.

Not only the car in front of you is decisive for the speed regulated by the adaptive cruise control. Based on location and navigation information, more and more cars independently reduce gas for bends, roundabouts and intersections. And autonomous parking is also becoming commonplace, even in cheaper cars. You no longer have to be in the car yourself for this, it is often enough if you are present nearby with your key or phone in your hand. If necessary, the car simply drives to you over a shorter distance in this way; then you do not have to walk through the rain across your driveway. All the signals that the car receives are now sufficient to be able to drive autonomously, the next step mainly requires enough computing power.

A matter of trust

It is impressive what all the electronics can do, yet it still applies that as a driver (even if you are standing next to the car with the remote control) you are responsible and therefore liable for the actions of your car. Therefore, the ADAS aids are only there to support you and you must be alert at all times, if only because even the best calibrated systems can refuse service due to a malfunction (a loose contact or a bug in the software) or dirt on a lens or sensor.

But whether the system works or not: are you as a driver actually still able to take your responsibility? With cameras and sensors, the car continuously monitors whether you are still paying attention. If the latter is no longer the case, the car ultimately brings itself to a controlled stop (after which the alarm center is alerted). That’s a safe idea. Yet not all systems contribute to a feeling of well-being. With some systems you can even wonder whether they do not overshoot their goal. Take, for example, the mandatory speed warning. It already starts beeping as soon as you drive one km/h too fast. Of course, rules are rules. But due to the small margin, the irritation factor is large, which is why many motorists switch off this type of system immediately after driving away. Too bad, missed opportunity. Furthermore, there are large differences between the manufacturers in the implementation and calibration of the various assistance systems. There are some who keep the car neatly in the middle of the lane (even if the route is not straight), detect other road users in time, steer around them with a smooth movement and, if necessary, brake nicely dosed. On the other hand of the spectrum there are systems that seem to react nervously and overstimulated to everything in their environment, make you doubt whether everything has been seen or do not perform tasks such as a simple lane change without giving a reason or break off halfway. As if an intern had to quickly finish the project on Friday afternoon. It makes that you dare to trust the ADAS systems almost blindly with one car, as a natural extension of your senses and limbs, while you prefer to leave the assistance with the other car for what it is and take matters into your own hands to achieve the European goals for 2030. If it is up to the forefront of the automotive industry, it should be possible, only not all manufacturers are in that forefront.

Mandatory assistance systems since July 7, 2022

Regulation 2019/2144 of the European Parliament states that the systems below are mandatory for all new cars since July 7, 2024. Cars whose type approval was issued after July 7, 2022 must already be equipped with them from July 7, 2022.

Emergency lane keeping system

Protection of the vehicle against cyber attacks

Intelligent speed assistance

Support for the installation of an alcohol interlock

Fatigue and attention warning

Event data recorder

And these since July 7, 2024

And cars whose EU type approval was issued after July 7, 2024 must also have the systems below since that date:

Advanced emergency braking for pedestrians and cyclists

Advanced distraction warning (avoiding distraction by technical means may also be considered)

In anticipation of automated driving, cars where that already applies must be equipped with the following since July 7, 2024:

Driver availability monitoring system

Systems that serve to replace the steering by the driver

Systems that serve to provide the vehicle with information about the condition of the vehicle and the environment

Systems to provide safety information to other road users

Independently in five steps

Based on the degree of automation, the SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) defines five levels of autonomous vehicles:

Level 1 : Assisted Driving

The car offers some assistance with driving, such as steering, braking or acceleration support, but the driver remains responsible.

Level 2 : Partial Automation

The vehicle can combine two or more aspects of driving, such as automatic steering and acceleration/braking, but the driver must constantly pay attention and be able to intervene directly.

Level 3 : Conditional Automation

The vehicle can completely take over certain driving tasks under specific circumstances (such as highway driving). The driver must remain available to intervene if the system requests assistance.

Level 4 : High Automation

The vehicle can drive completely independently in certain circumstances (for example, in specific zones or under favorable weather conditions). A human driver is not needed in these situations.

Level 5 : Full Automation

The vehicle can drive completely independently under all circumstances, as a human would. No human intervention is required, and even a steering wheel or pedals are not necessary.